|

Susan is the Founding Director of inVIVO Planetary Health – an initiative established in 2012, as a Worldwide Universities Network (WUN) in response to the 2011 WUN Shanghai Declaration ahead of the United Nations General Assembly on NCDs (noncommunicable diseases).

Concepts of planetary health denote the interdependence between human health and place at all scales. In modern times, these concepts emerged from the environmental and preventive health movements of the 1970s, including theFriends of the Earth. It was not until 2015 that these concepts have been more broadly popularised with the advent to the Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on Planetary Health. However, Planetary health is not a new idea; it is an extension of a concept understood by our ancestors, and First Peoples.

In 2018, following the 7th annual conference in Canmore, Alberta, Canada, inVIVO provided the Canmore Declaration, a Statement of Principles for Planetary Health. This expands upon the 1986 Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion and affirms the urgent need to consider the health of people, places and the planet as indistinguishable.

|

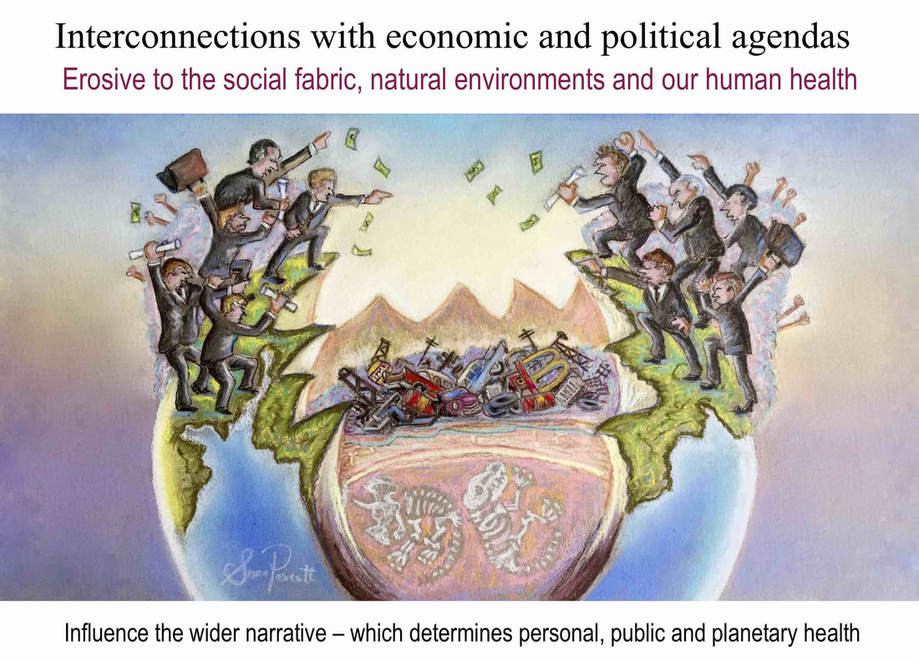

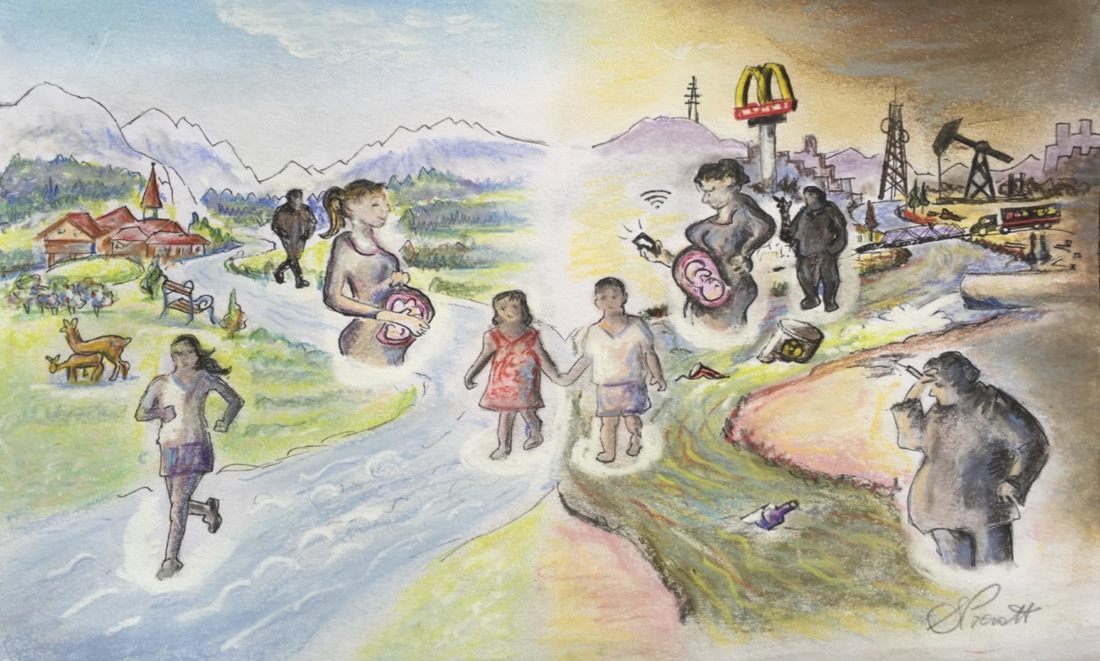

Just as virtually everything on earth is ultimately interconnected and interdependent, so are the many of the problems we face today. This means that the causes and the solutions cannot be considered in isolation We need to view the health of our global society, our global economy, and our global environment as ultimately part of the same shared global agenda which affects all of us. With these perspectives, we have the best chance of finding convergence of purpose, and convergence of vision, ultimately for implementing more integrated plans of action. For that we need to recognise the interconnections and the fundamental common driving elements. The root causes.

The 10 Principles of the

|

1. The sustainable vitality of all systems: Planetary health, inseparably bonded to human health, is defined as the interdependent vitality of all natural and anthropogenic ecosystems; this vitality includes the biologically defined ecosystems (at micro, meso and macro scales) that favor biodiversity; it includes the more broadly defined human-constructed social, political, and economic ecosystems that favor health equity and the opportunity to strive for high-level wellness; this definition also includes the business ecosystems that influence sustainable and health-promoting local and global commerce.

2. Values and purpose: Attitudes, values and behaviors, and relationships sit at the heart of reaching planetary health goals; that is, human vitality (wellness) depends intimately on planetary vitality that in turn depends on humankind, on human kindness, empathy, mutualism, responsibility, and reciprocity at the individual, community, societal and global levels; thus, achieving planetary health must be a product of the interconnected systems of life and the approach to living (lifestyle)—the bios and biosis, respectively.

3. Integration and unity: Planetary health is rooted in ancestral concepts of the unity of life; the complexity of the challenges we face demands integrationist approaches; responsibility for planetary health requires us to relinquish conventional professional, societal, and cultural partitions and to develop contextual coalitions based both on science and broader cultural narratives.

4. Narrative health: Promoting awareness and discourse toward solutions (including those emerging from science) demands a narrative-based process that includes traditional knowledge and sciences and an understanding of the power of language; in healthcare, this underscores a role for researchers, clinicians, public health physicians and health promotion professionals in engaging patients and the community-at-large (and their influencers, policy makers and political representatives) to underscore the importance of the earth’s natural systems and biodiversity to human health and well-being.

5. Planetary consciousness: Planetary health requires commitment to self-awareness, cultural competency, and critical consciousness; to reduce the ways in which social, economic and political systems oppress groups and communities in different (and unequal) ways; to challenge contextual power hierarchies that block health equity; and to correct sources of misinformation that stand in the way of well-established personal, public and planetary health practices

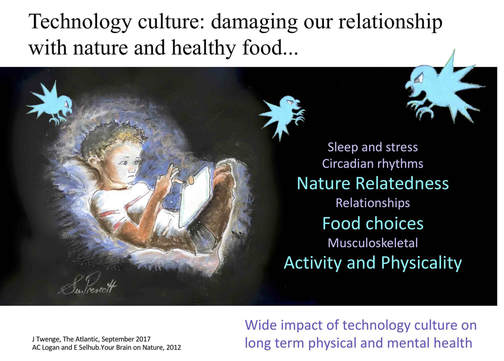

6. Nature relatedness: We should educate on the importance of emotional connections to the land, to nature and its biodiversity; consider the psychological asset of nature-relatedness in clinical settings and beyond; encourage further research directed at understanding how mental and emotional relationships with place and planet are developed, and the biopsychosocial implications of experience (or lack, thereof) with nature.

7. Biopsychosocial interdependence: In the context of personalized/precision medicine, where possible we should promote understanding of our dependence on the natural environment around us (flora, fauna and our physical world) and intimately part of us (the human microbiome); use opportunities to illustrate and educate on how physiology (in health and disease) and dysbiosis (as a measurable microbial construct, and a metaphor from its Latin roots ‘life in distress’) can be linked through ecosystems operating from the micro to macro scales (e.g., misuse of antimicrobials, low-grade inflammation and/or the microbiome).

8. Advocacy: We should advocate for greater inclusion of the planetary health perspective in the training of all healthcare professionals; advocate for early-life education in sciences that 1) illustrate the interconnectivity of human life with the Earth’s biodiversity and its natural systems; and 2) illustrate how individual wellness is predicated on our way of living with other humans, and other forms of life. Such discourse should be encouraged and included in the education of caring and teaching professionals (and widely throughout society), such that individuals will strive to lead by example, to reduce primacy and encourage unity.

9. Countering elitism, social dominance and marginalization: Planetary health requires greater awareness of the impact of authoritarianism, and strong advocacy against collective narcissism, hubris, and social dominance orientation, factors that otherwise reduce empathy, marginalize out-group voices and impede the World Health Organization’s stated goals for global health promotion; research across all domains should occur with meaningful community engagement and partnerships that carefully consider the motivation and the beneficiaries of the research agenda.

10. Personal commitment to shaping new normative behaviors: We should strive to live by example: in clinical/academic/public settings and beyond we should endeavor to include the principles and practices of a planetary health lifestyle; in daily behavior, we should aim to be part of the solution, not the problem; remain committed to a planetary peace agenda; encourage mutualism, empathy and community cohesion; and underscore that aggression, conflict and violence are destructive to person, place and planet.

|

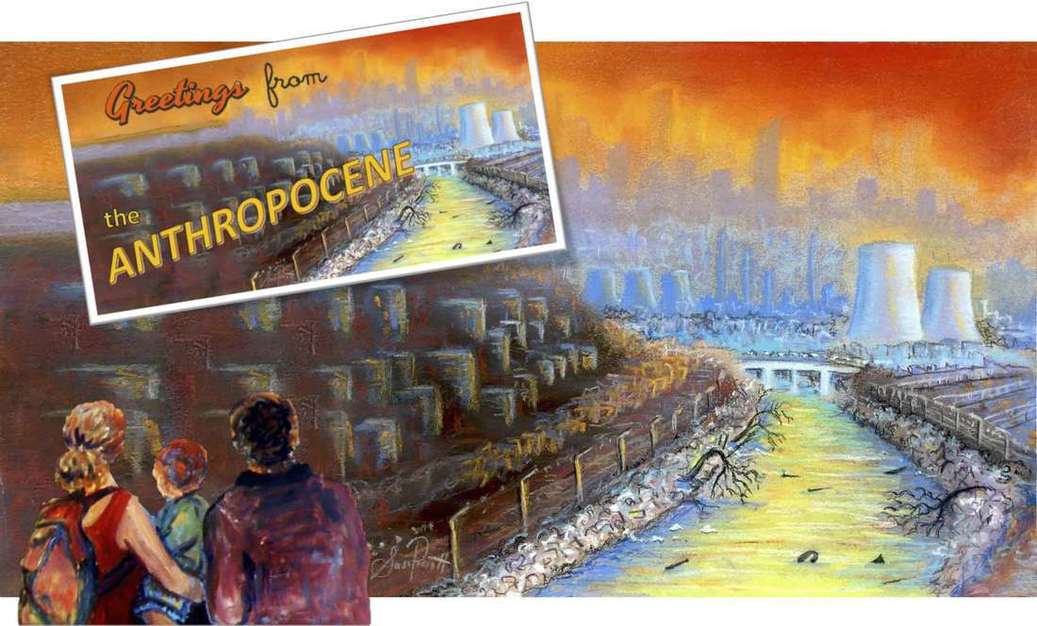

We are living in a period of the earth’s history that we have defined as the ‘Anthropocene’ – a name derived to reflect the increasing human dominance over planetary systems and the relative stability of the Holocene, with geological upheaval and extensive disruption of the biosphere resulting in accelerated biodiversity loss, bioaccumulation of toxic materials and disruption of global rhythms and climatic patterns. This has thrown the natural rhythms and relative balance of many planetary and ecological systems into uncertainty, unpredictability and genuine chaos. We have liberated lithospheric chemicals, mobilised radioactive materials and generated synthetic substances which now contaminate our air, water and food supply, and threatened our own health. We have progressively eroded the natural resilience of ecosystems, with the loss of many species more vulnerable than our own

|

Our impact on the planet has been nothing less than titanic in magnitude, force and power” |

Human activity and economic systems are driving dysbiotic drift” |

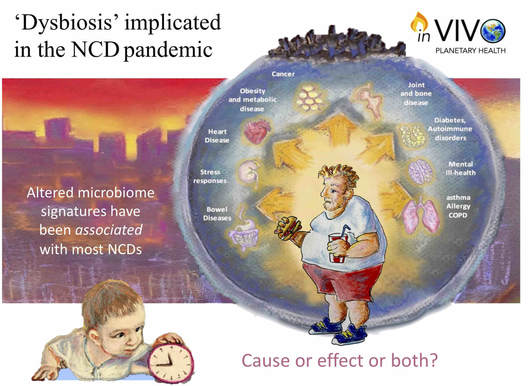

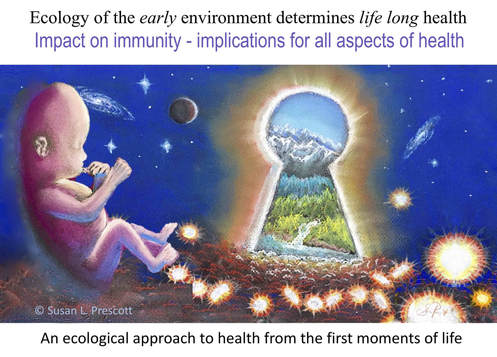

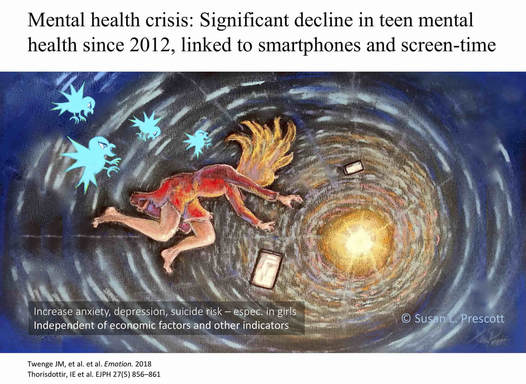

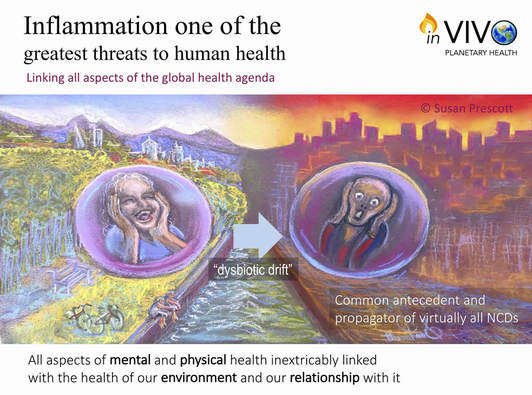

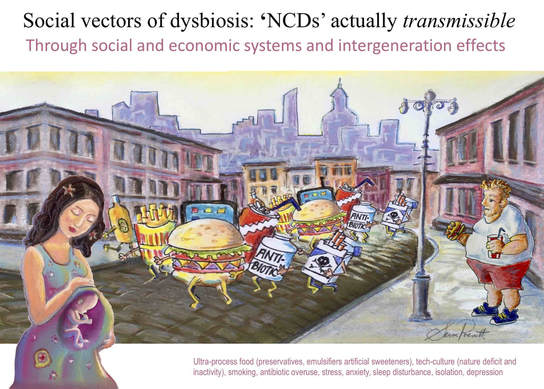

Progressive loss of biodiversity in the environment around us is already affecting human health. Not only through the quality and diversity of our food, and the physical and mental benefits of being in nature, but also the biodiversity of the environment within our bodies. Only recently have we realised that loss of species from the vast microbial ecosystems within the human body is another factor eroding human health. Alterations in species diversity of bacteria in the human gut in progressively cleaner modern environments is implicated in metabolic disease, immune disease and mental health disorders. Together, the enormous pressures of stress, unhealthy nutrition, pollution and lost biodiversity are driving a pandemic of human disease affecting both our physical and mental health. The pandemic of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as cancer, diabetes, heart disease, obesity, mental ill health, and many other chronic diseases, is directly linked to social, environmental and lifestyle changes in the last century.

|

Read more in our Paper:

Immune-Microbiota Interactions: Dysbiosis as a Global Health Issue.

Immune-Microbiota Interactions: Dysbiosis as a Global Health Issue.

Environmental degradation has direct implications for the diversity of human microbes ...and our health” |

As we become progressively more ‘westernised’ there is evidence of ecological ‘extinction of microbes’ including our own. For example, some species of bacteria that reside in intestines of the dwindling populations of traditional hunter-gatherers on Earth today, are no longer evident in Western populations, or are reduced below detectable functional levels.

Most of the factors we already know are eroding human health, are also adversely affecting our microbes - including pollutants, antibiotics, changes in agricultural practices, unhealthy, highly processed foods, stress, alcohol, physical inactivity and disruption in sleep and circadian rhythms (light pollution at night). These factors are all driving ‘dysbiotic drift’. The commercial forces that promote consumption of unhealthy products (alcohol, tobacco, unhealthy foods) are adding to both environmental burden of production and the economic costs of the diseases that they produce. |

|

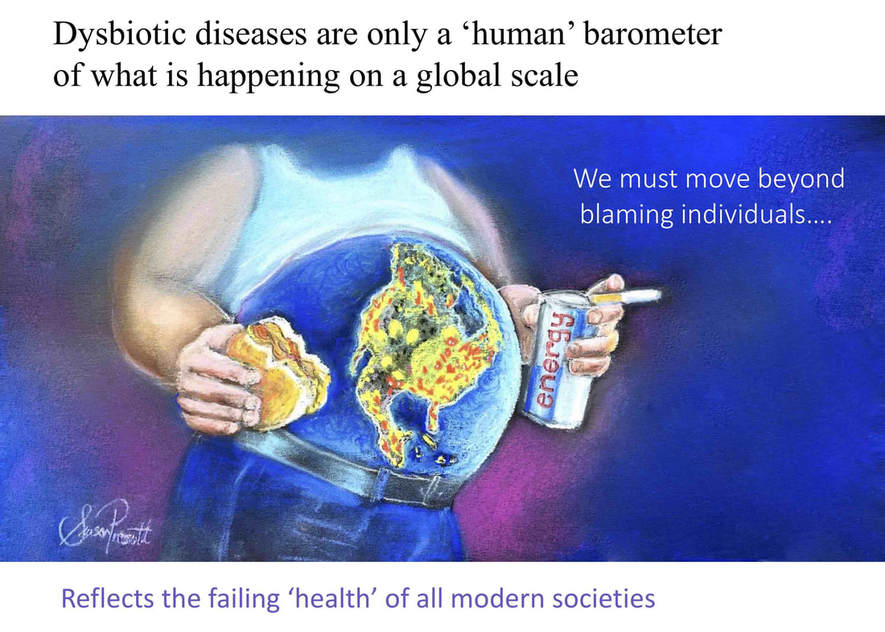

The implications of the microbiome extend to virtually every branch of medicine, biopsychosocial and environmental sciences. This is directly relevant to broader discussions concerning rapid urbanization, antibiotics, agricultural practices, environmental pollutants, highly processed foods/beverages and socioeconomic disparities--all implicated in the NCD pandemic. Addressing the “upstream“ drivers of health and human potential is critical. These operate widely to influence both the health of environments and the health of individuals (and their opportunities and choices) across life. Restoring what is missing is as important as reducing adverse exposures. Making every effort to overcome the greater burden in disadvantaged populations is a matter of social justice.

|

Ecological justice: We need to address the 'upstream' determinants of health across the life course and not blame individuals or even communities” |

Read more in our Paper:

Transforming Life: A Broad View of the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease Concept from an Ecological Justice Perspective